How to Make EVs Affordable to More Consumers

To expand electric vehicles (EVs) beyond early adopters, we need to make EVs equitably accessible and affordable to more Americans. This requires two core types of incentive programs: 1) incentives for buying new EVs, including increased incentive amounts for low- and moderate-income consumers and 2) incentives for buying used EVs.

To achieve equity goals, these incentives must be provided at the point of sale, rather than as a tax credit, they must be stackable with other incentives provided by utilities or other entities, and there must be meaningful community engagement.

EVs made up less than 1% of all new vehicle sales in the U.S. in the past decade. But that is poised to change.

Consider this: Automakers are pledging to produce more types of EVs and some even plan to phase out fossil fuel vehicles; oil companies and EV companies are partnering to offer EV charging at gas stations; utilities are building EV charging infrastructure; and several U.S. states are vowing to end the sale of new fossil fuel vehicles as early as 2030.

Using Caret®, the Center for Sustainable Energy’s data-driven platform for modeling EV incentives, we can outline some clear paths for accelerating EV adoption efficiently and equitably through EV incentive programs.

- Increase incentives for low- and moderate-income consumers to buy new EVs.

Incentives are essential to EV market transformation. Providing an extra incentive for low- and moderate-income buyers, including the ability to stack incentives offered through different public and private programs, can make some new EVs more affordable. For example, a low- to moderate-income buyer of a battery electric vehicle (BEV) in the San Joaquin Valley, a mostly rural area in central California, could stack up various incentives last year to reduce the price of a new car by a total of $14,000.

Using Caret’s Affordability Calculator, we can model how different types, amounts and durations of EV incentives can make specific models of EVs affordable to households at various percentages of the federal poverty level (FPL). Using 400% FPL, the eligibility threshold used in the federal health insurance marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act and in multiple California EV equity incentive programs, Caret’s modeled outputs can also be compared, for instance, to the 40% equity benefit goal articulated in the Justice40 Initiative.

- Expand EV incentives to used vehicles.

More Americans (typically 56%) buy used light-duty vehicles (cars, pickup trucks, SUVs) than new vehicles. Used vehicles are more likely to be purchased by lower-income households while buyers of most new vehicles tend to be male, white and higher income homeowners.

To appeal to the larger group of used vehicle-buying consumers, a robust used EV market needs to be developed.

States that have led the way in sparking EV adoption have focused on new EVs. This was likely for a number of reasons, including that when these initiatives began there was, practically speaking, no such thing as a used EV. This is no longer the case.

With the average new car lease lasting three years, a used EV market is starting to develop. (Here’s a sampling of used EVs available today in Los Angeles.)

The Oregon Clean Vehicle Rebate Program is the first statewide incentive program in the U.S. to offer rebates specifically to low- and moderate-income applicants for used EVs. Connecticut’s EV incentive program, CHEAPR, which CSE administers, recently added a used EV incentive and we expect more will follow. Several utilities, including Southern California Edison and Xcel Energy, also offer or plan to offer used EV incentives.

- A point-of-sale incentive is superior to a tax credit to expand equitable access.

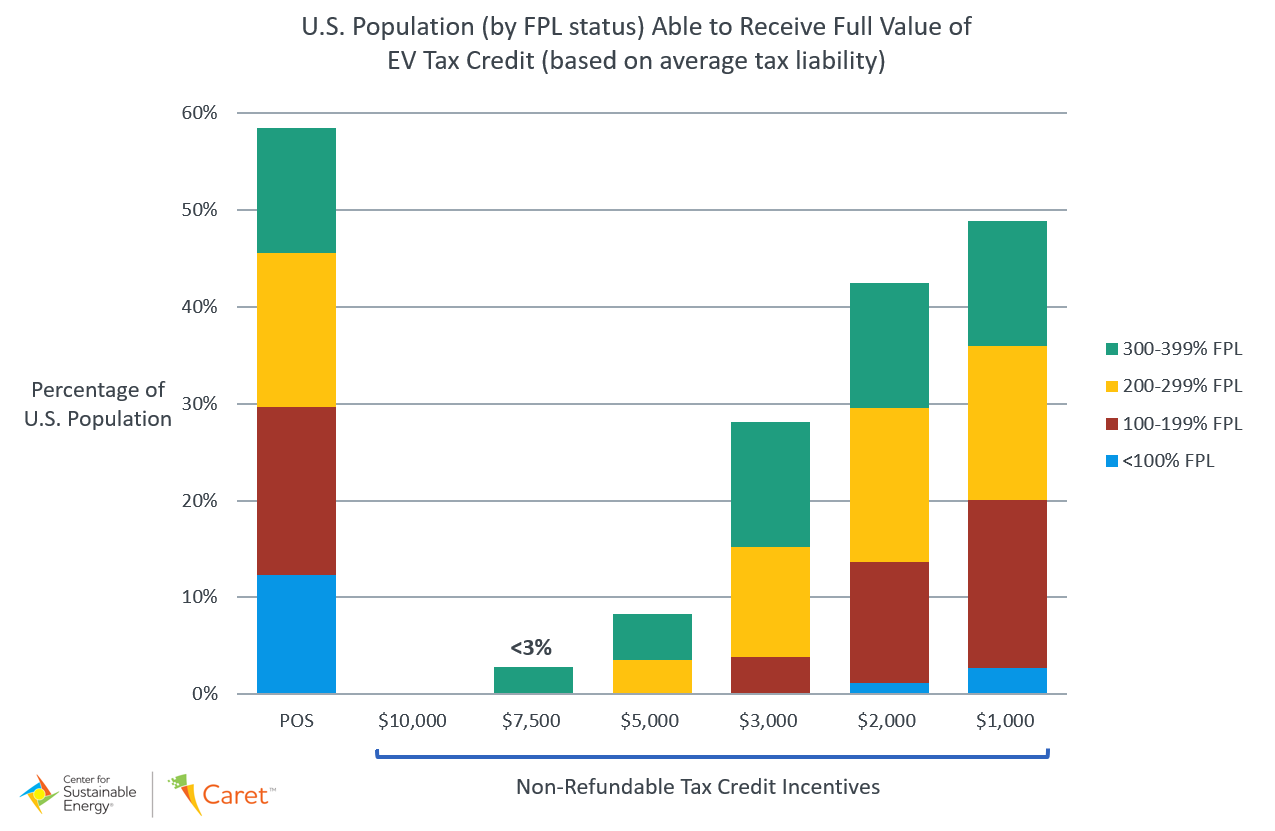

Who is eligible for the current federal $7,500 EV tax credit? People who have that amount of tax liability.

For example, if you purchase an EV eligible for the $7,500 tax credit, but you owe only $3,000 in federal taxes, you will only receive a $3,000 credit. CSE’s analysis of the tax liability of Americans with incomes at or below 400% FPL reveals that less than 3% of this group would be able to use the entire $7,500 tax credit unless it were made fully refundable.

Providing an EV incentive at the point of sale eliminates a car buyer’s uncertainty over whether they will ultimately qualify for a tax credit and eliminates the wait.

Studies show consumers discount the value of future benefits, like tax incentives, which reduces the impact the incentive has on their decision-making process. A 20% discounting is the midpoint value of the discounting range discussed in the literature. In other words, $80 today, in consumers’ minds, has a higher face value than $100 they would have to wait to get at a future date.

Adverse impacts associated with tax credits could be counteracted if tax credits are made fully refundable (so the value does not depend on the consumer's tax liability), fully advanceable (so recipients do not have to wait), and transferable (so they can be applied as down payments toward the vehicle cost at the time of purchase).

- Meaningful community engagement and partnership is crucial.

These types of EV incentives are a step in addressing the historical underinvestment in disadvantaged communities and the disproportionate health impacts from pollution they continue to face. For these programs to be successful, two equity policy and program components are crucial:

- Meaningful engagement of disadvantaged communities, communities of color, and rural and tribal communities, and

- Genuine partnerships with community-based organizations.

Shared, accessible and inclusive decision-making processes help a program effectively communicate with and reach the people in these communities, address their needs and implement community-identified solutions. Doing this will ensure that as we work to build a cleaner, sustainable and resilient future for all, investments in EV incentive programs prioritize and embed equity.